Engineering my family's spending

One of the areas for improvement I brought up in my 2022 review was finances.

I have very specific goals for my family's financial future and, in order to reach those goals, we'll have to optimize three aspects of our finances: earning, spending, and investing.

It's easy to fall into the trap of focusing on just one side — trying to earn more. As my own income has grown over the decades, along with my spending, I've realized how profoundly wise my grandmother was when she kept repeating this one truism:

"It's not about the big income, but the small expenses."

It's been eight months since I wrote that yearly review and I've made a lot of progress since then. We're not all the way yet but at least we're moving in the right direction and I'd love to share my current approach. Hopefully, it can help someone else grow rich as well!

NB! I use Mr. Money Mustache's definition of the term — living a rich life. Don't expect to see me flying around in my private jet anytime soon.

My improvements to our spending rest on two fundamental principles:

- Intentionality is crucial for long-term improvement.

- Feedback loops are crucial for staying intentional.

In practice, that means we first plan how we want to use our money and then continuously evaluate how we actually end up using it. Together, these two sides create a virtuous cycle.

Let's look at both principles in turn.

Principle 1: Intentionality

Jeff Olson described in The Slight Edge how we're all headed in one trajectory or another, in all aspects of our lives. For example, you might be putting in extra hours at work and crushing it in your career, while skipping exercise and having your health decline.

The main argument in Mr. Olson's book is that if you're not consciously deciding and working on a specific trajectory, it'll most likely default to a bad one, which compounds over time. Thankfully, very little effort is required to turn that around (e.g. the slight edge).

"How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives."

— Annie Dillard

Apart from our innate laziness and proclivity for short-term rewards, many external forces also conspire against us having a positive, financial trajectory.

Cal Newport hammered this home in Digital Minimalism and it bears repeating: marketers are working day and night trying to change your behavior to benefit them, and companies are investing a lot of money in research to maximize your spending with them.

The best way to combat this influence and to take charge of your finances is to become more intentional about how you live your life and how you spend your precious, finite resources. But how do you practically do that?

One thing that transformed my own approach is YNAB's first rule: Give every dollar a job. When money comes in, you allocate every single cent of it (or, rather, Swedish "öre") to a specific purpose.

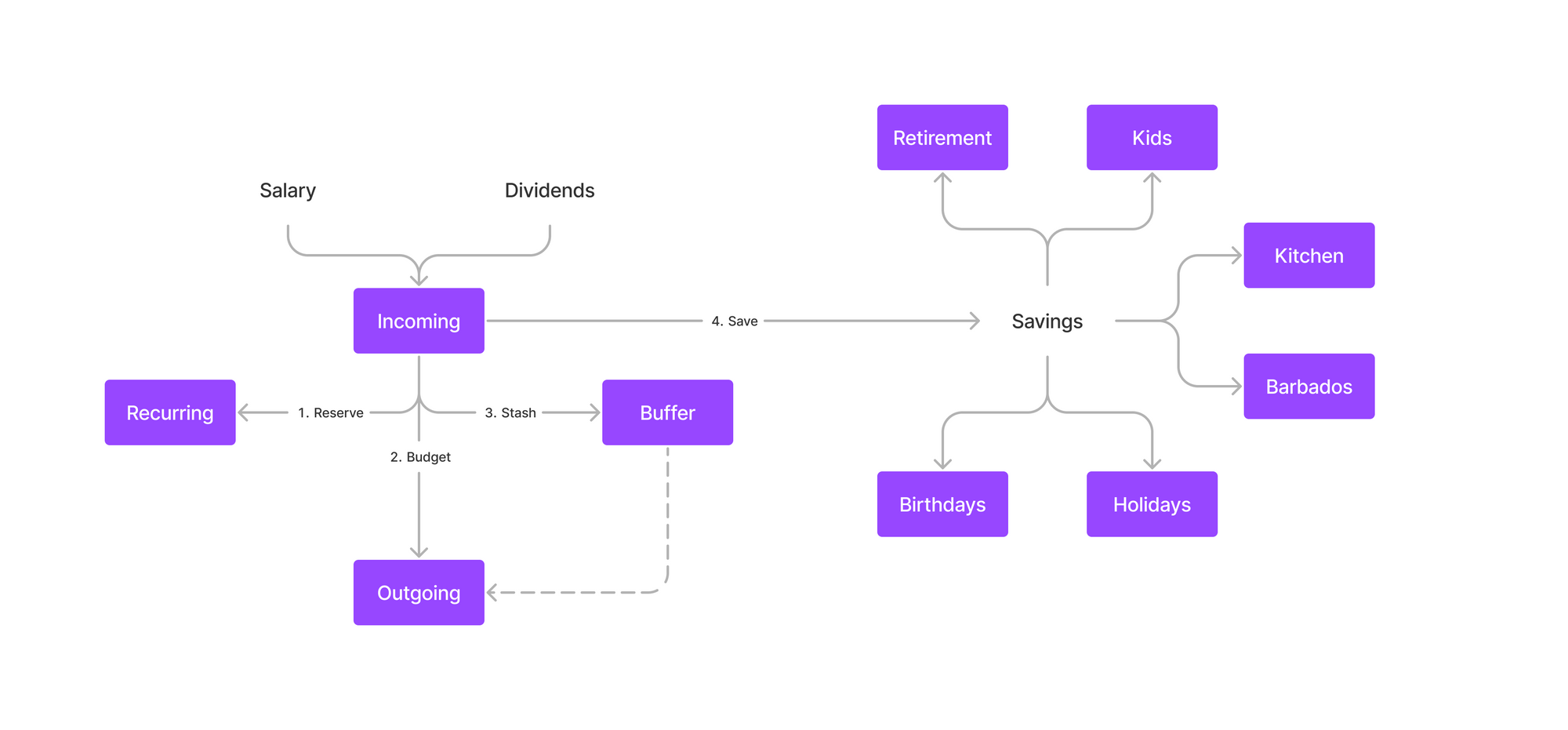

My current process for doing this might initially look complicated, but bear with me! It's actually quite straightforward. With every transfer to our Incoming account, I run through this four-step checklist:

- Recurring costs. I reserve money for essential costs, including things like mortgage, car lease, Netflix subscription, etc.

- Outgoing. I estimate how much we'll spend on groceries, cinema, and other highly variable, non-recurring spending. This is where we've made — and continue to make — the biggest difference in our ongoing finances.

- Buffer. I stash money away for unforeseen events, in order to create a financial opportunity and a cushion for when shit inevitably hits the fan.

- Savings. Finally, we put away the rest for bigger expenses in the future: our pension, buying a house, renovating the kitchen, traveling to the Bahamas, etc.

This allocation usually happens on the 27th, two days after the monthly payday in Sweden, so as to allow for automatic transfers and payments to be completed. Sometimes money arrives from other sources, on other occasions, but the four-step process remains the same.

This is what it looks like (the purple boxes are our different bank accounts):

NB! With the help of the amazing YNAB app, we could put everything in one and the same bank account. This is partly a legacy of the dark time before we started using YNAB and partly an attempt to mitigate potential damage, if one of our debit cards were to end up in the wrong hands.

First step: Recurring costs

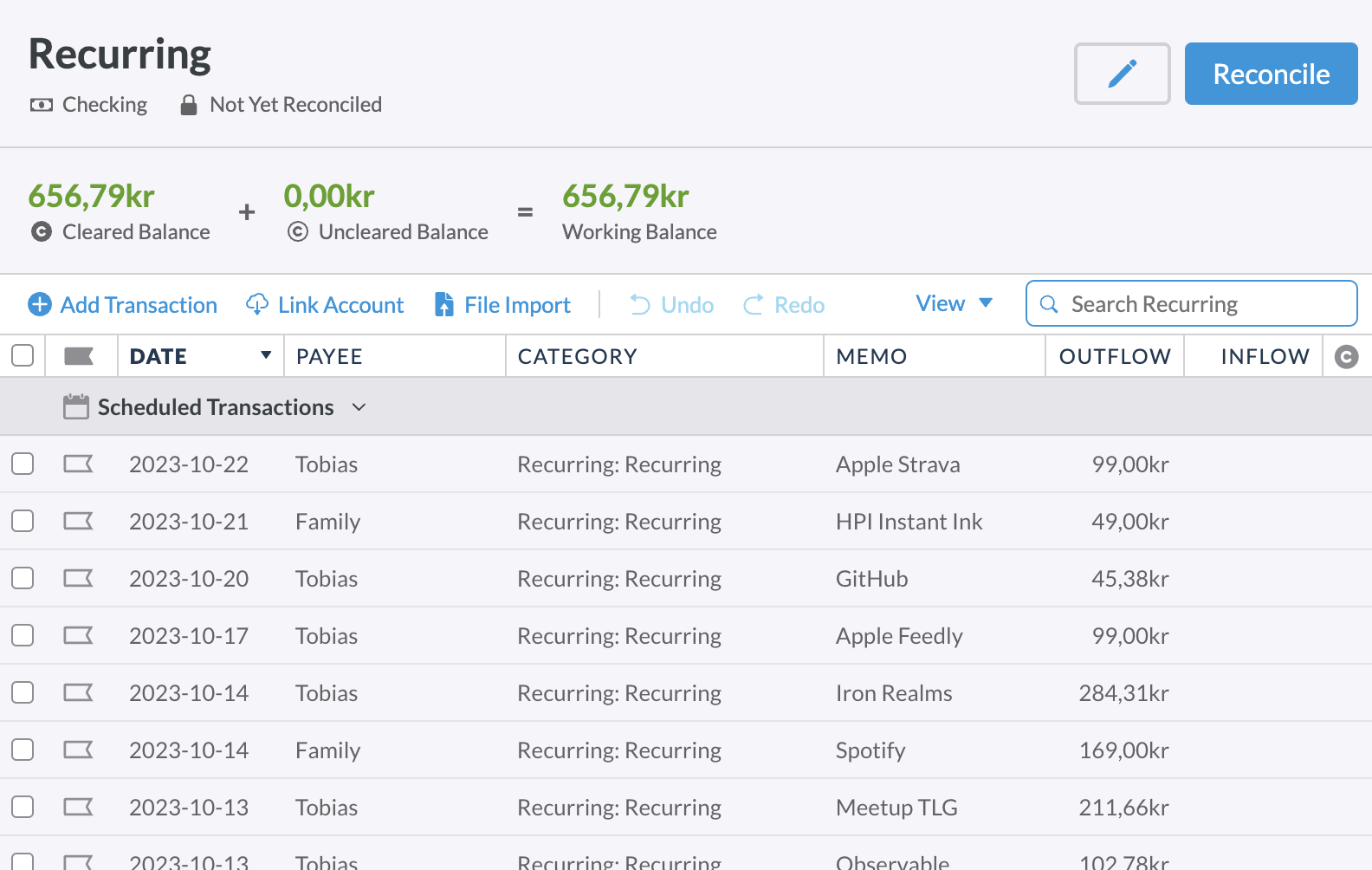

I track all our recurring costs in YNAB, as repeating transactions; car lease, Internet connection, YouTube Premium, monthly donations, app subscriptions, etc, etc. Each is marked for a specific day of the month and YNAB helpfully prompts you to check it off when it's due.

We currently have 37 continuous expenses and all of them are tied to a dedicated bank account, connected to a separate debit card, giving us a clean partitioning and complete control of all our running expenses.

This gives us two important benefits:

- I know precisely what we're paying for every month and how much each costs. It's easy to find expenses we can cut if we want to lower our costs, which has been very helpful during the last year of steadily increasing interest rates.

- I immediately notice if an expected payment hasn't gone through, for whatever reason, so that I can be proactive about it. No reminder fees on my watch!

Because of fluctuating currency rates, shifting interest rates, inflation-driven markups, and other variabilities, I make sure there's an extra 10% on top of the total sum of our costs. This margin for error is a cheap price for peace of mind.

Second step: Outgoing

On top of the known, recurring costs, we have something of a catch-all category of expenses for simply living and enjoying life. These are lumped together in another, separate bank account, to which our daily-use debit cards are connected.

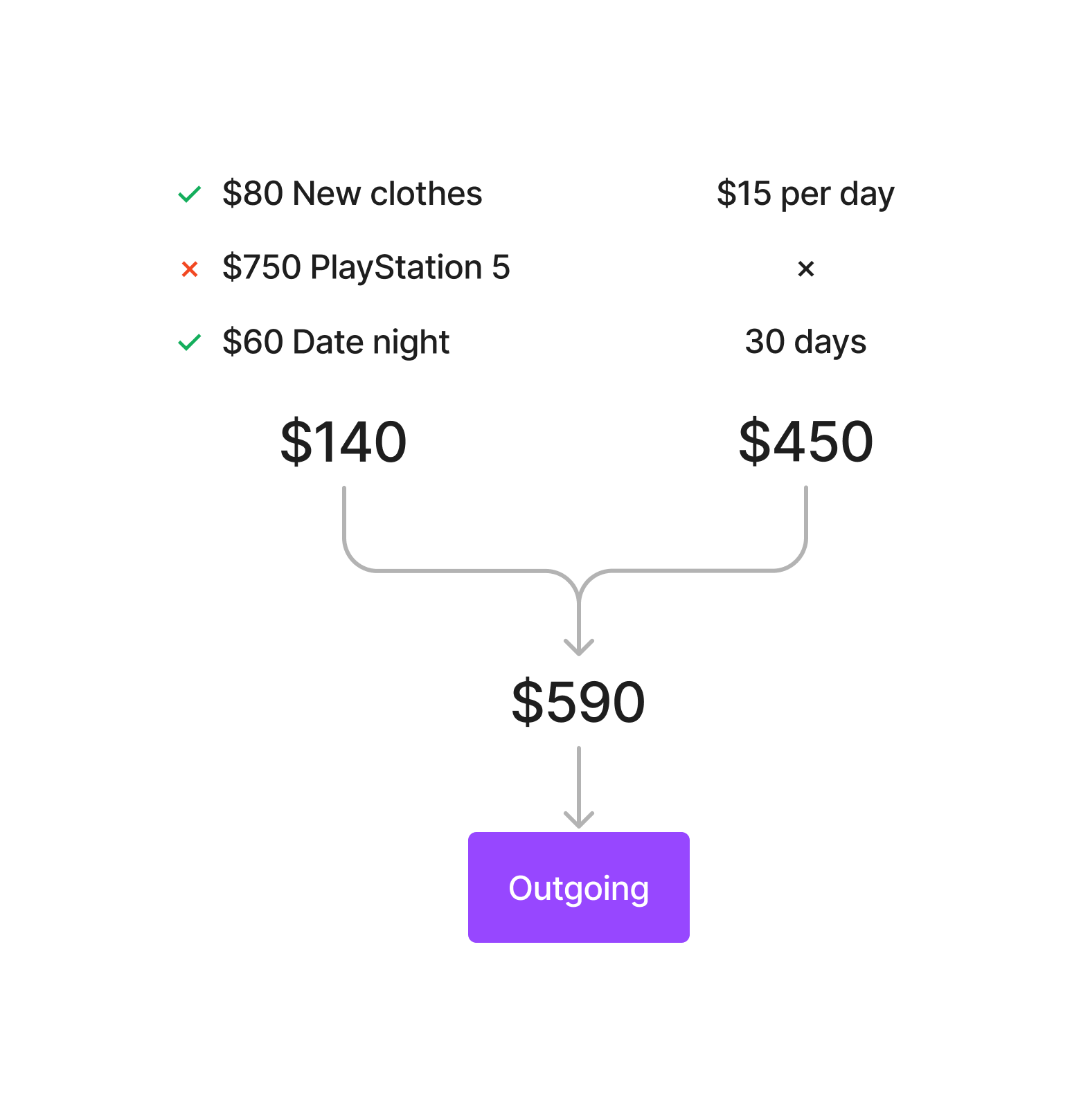

The amount allocated here is a rough estimation and comes from 1) the sum of our planned expenses and 2) the product of our daily living expenses.

We keep a shared list of planned expenses; things we'd like to buy or spend money on — new clothes, a movie at the cinema, date nights, dentist appointments, etc. When allocating money to our Outgoing account, we first do a brain dump to see if there's anything we'd like to add to our list of planned expenses, and then we pick which things we actually will spend money on the coming month.

The sum of their costs is added to our "Daily" category in YNAB and the money is moved from our Incoming to our Outgoing account, so it's readily available.

A nice side benefit of having this list is that it helps us defer spending money, without feeling that we're denying ourselves anything. If I want to buy a PlayStation 5, I simply add it to the list and it'll be evaluated against all the other things we'd like to buy. (So far, many other things have felt way more important but maybe one day!)

Next, we decide on a daily budget and multiply that by the number of days until the next salary. This is supposed to cover things like groceries, snacks, impromptu café visits, etc. We continuously try to challenge ourselves here, by seeing how little we can get by on, but it's a balance. For long-term success, we take care not to make ourselves feel too denied in our day-to-day lives.

If we decide on $15 per day and there are 30 days in the month, then we add another $450 to our "Daily" category in YNAB and move an equal amount of money from our Incoming to our Outgoing account.

Third step: Buffer

Mike Tyson once said, "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth." This is equally true for personal finance. Shit inevitably happens, which is why I like to own a generous supply of proverbial toilet paper.

On one hand, it's incredibly hard to predict all your expenses and, on the other hand, a huge reason why we're being so zealous with our finances is to enable spontaneity. Jocko Willinks explained it well in his book Discipline Equals Freedom — by having a strict baseline, you give yourself incomparable liberty the rest of the time. This applies to all aspects of our lives.

I live in Sweden with my family, where we are blessed with an incredible social safety net that takes care of any would-be medical emergency. Scraped your knee and need a professionally applied bandaid? That's $20, thank you. Require a double-bypass surgery and six weeks of hospital care? Yup, that's $20 just the same. We do pay our fair share of taxes but when something bad happens, you're taken care of.

There are other unexpected expenses, however. Things occasionally break down and have to be repaired or replaced, or you get an unforeseen bill that hasn't been budgeted for. On the flip side, some friends might organize a spontaneous weekend getaway or your favorite artist could announce a concert you didn't know about.

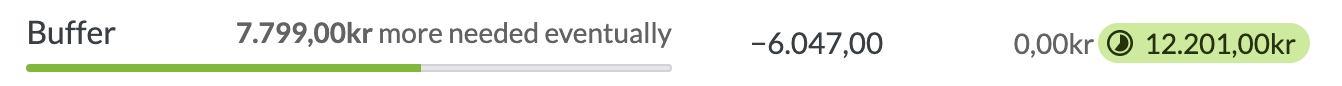

To both mitigate emergencies and be able to take advantage of opportunities, without having to go into debt, we keep a sizable buffer — a separate bank account with the intention to never have to be used.

Some people take quick loans or buy things by paying in installments, incurring costly and needless interest. Something for $150 might end up costing $200 for this reason. Or they don't buy it at all, turning resentful of their finances instead. Our buffer helps us avoid both!

We try to always keep our buffer at a set amount of money — a completely arbitrary sum, which we feel would cover the vast majority of emergencies.

Fourth step: Savings

One of the first pieces of advice you hear when dipping your toes in the world of personal finance is to put away money for savings first, before spending it on anything else. It's a great principle and I follow it, with a modification.

The reason people give this advice is to combat Parkinson's Law:

"No matter how much money people earn, they tend to spend the entire amount and a little bit more besides. Their expenses rise in lockstep with their incomes."

Basically, if there's money in an accessible account, you'll most likely end up spending that money. By removing part of that money as soon as it arrives in your account, and putting it away into savings, you'll adjust your behavior to the new amount without feeling any worse off for it. (With the added benefit of having grown your savings.)

Since I use other mechanisms to combat frivolous spending (as per the previous steps), I allow myself to allocate savings at the end of my process.

When I get to this last step, I distribute the remaining amount in specific "buckets". They are tied to determined goals, like renovating the kitchen, traveling to Barbados, celebrating birthdays, etc.

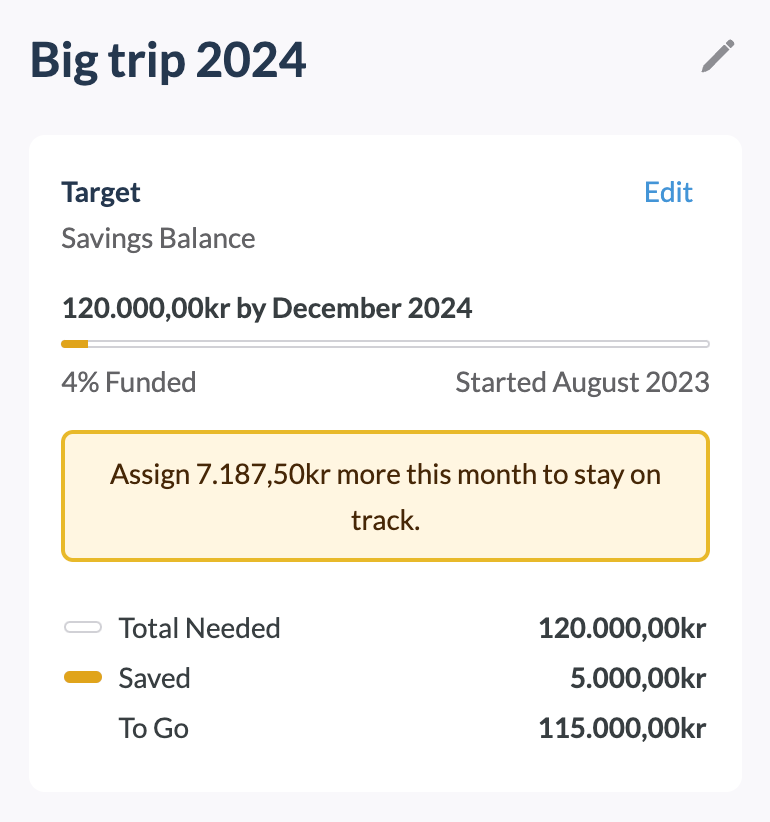

I've recently started to add these saving goals to YNAB, where you can set a target amount and deadline. With that, the app can help calculate a minimum monthly savings amount to stay on track.

NB! I see investments as something distinctly different from savings; in particular more long-term and vague in their goals. I handle those before anything else, even prior to this whole allocation process, by purchasing a set of index funds every month. We've got one investment account for me and my wife and another for our children.

Principle 2: Feedback

Feedback is a fundamental process for human development, without which nothing could reliably improve. Kids see a candle burning and can't help but touch and be burned by it. This feedback teaches them to not touch fire (with the exception of my own children…)

The same mechanism holds true in many areas of our lives: we perform an action, experience a reaction, and learn from that. This is how we improve our future actions.

The reactions can sometimes hurt (negative reinforcement) or they can make us feel good (positive reinforcement. We need both parts to improve.

Unfortunately, our stoneage brains require faster feedback than what we often get. You can blip your plastic debit card and immediately receive a new iPhone as a reward, the pain of parting with $999 arriving way later.

Our family uses YNAB to shortcut this process, by creating more rapid feedback.

Budgeting feedback

One way is by adding every purchase directly to the mobile app. When we've gone crazy in the Asian store and our monthly budget drops from $450 to $350 in the blink of an eye, then it hurts at the precise moment when we can learn from it.

Often, we can avoid the pain by checking the budget while we're in the store, then putting back eight of the ten different sauces we've just grabbed.

One other way we use YNAB for this is by recalculating our daily budget. With $450 to spend over 30 days, we've got $15 per day. If we spend $100 on the first day, then we're left with only 350/29 = $12 per day for the remainder of the month. Or if we avoid spending at all for the first two days, then our daily budget bumps up to 450/28 = $16 per day.

I do this (almost) every morning — updating YNAB, calculating our daily budget, and then texting to my wife our new daily budget. It almost becomes a game, because we know that if we manage to stay under or happen to go over the budget, we'll experience the effects accordingly the very next day.

Positive reinforcement

With all this strictness and total control, I think it's important to not feel deprived in your everyday life. There will be peaks and valleys but if the baseline makes resent your lifestyle, then you won't last very long. And "growing rich" is all about the long, long game.

In my online fitness coaching, one of the most telling signs that a client will enjoy long-term success is whether they intelligently adjust their life to mitigate inevitable hurdles, or if they simply grit their teeth and expect to overcome everything by sheer willpower. Some you can, some you can't, and a few occasional failures are all it takes to derail progress.

Even if you're following your very own rules, despite really wanting to reach the end goal, it's imperative that you find a balance that will help you run the distance, without risking anything unnecessarily.

I mentioned negative and positive reinforcements before, which are the two sides you need to balance. Don't worry about the negative — it'll appear by virtue of money being a finite resource — but do take care to implement some positives!

Add nice-to-haves to your budget.

It doesn't have to be expensive per se but make sure your budget reserves money for treats, strewn throughout the month. I buy the extra nice protein powder, my wife does her nails, we get more books for our library, etc.

Also, celebrate your progress.

I create a report in Observable every month, where we track our total net worth, growing assets, shrinking debts, total spending, and so on. It both highlights what we did well the previous month and how we're improving our financial state, and it projects our future goals based on the current trajectory.

(Basically, it's a regression analysis of the past one, three, twelve, and twenty-four months. Let me know if you're interested and I'd be happy to elaborate on that report.)

It's incredibly satisfying to see how we're improving, month by month and year by year. The impact of a single month might look puny in itself but, accumulated and compounded over time, every little part is a powerful addition to something big.

You don't have to run to get somewhere worthwhile. As long as you're intentional about it, so as to make sure you're going in the right direction, then walking comfortably will take you somewhere good.